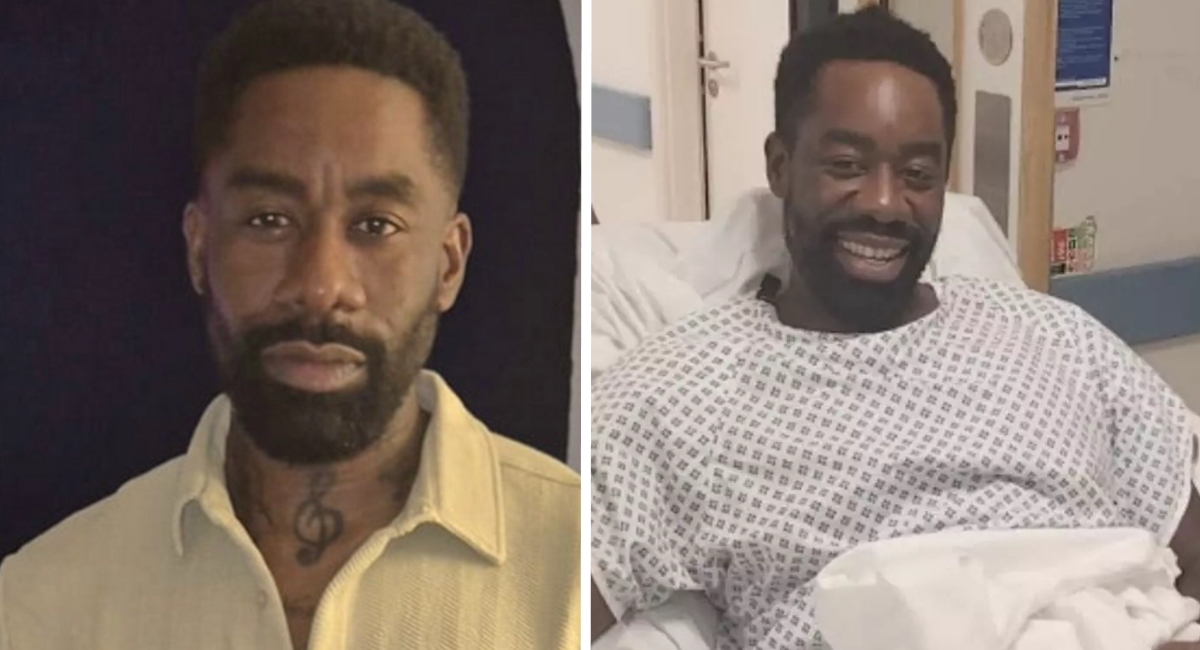

At 42, Matthew Allick was fit, on a night-shift schedule, and proud of his healthy habits — until one unremarkable day, climbing a single stair felt like summiting a mountain. Within moments, he flatlined: zero pulse, zero heartbeat. He lay that way for ten minutes. When he finally woke up, he didn’t remember angels or tunnels; he remembered peace. “It felt like I’d just woken from a calm, deep sleep,” he recalls — a phrase he now repeats whenever someone asks what it felt like to come back from death as vividly recounted in UNILAD’s story.

At first, the symptoms were subtle — shortness of breath, swollen feet. He blamed his night shifts. But when he couldn’t climb one step, his colleague called an ambulance. Arriving at the hospital, he described his pain as an “11 out of 10,” then “13,” and then… nothing. He didn’t just faint — doctors confirmed he was clinically dead. CPR delivered with such force it caused internal bleeding, then a coma. Ten minutes without life support later, a defibrillator jump-started him back to life. Breath returned. Pulse returned. And for Matthew, something unexplainably familiar poured back into his consciousness covered in detail by UNILAD.

The phrase “coming back” can feel grandiose — but Matthew doesn’t wax poetic. He says, “I don’t remember anything from when I was dead … but waking up felt exactly like a gentle awakening from sleep.” That contrast between dramatic collapse and serene lucidity is what made his story resonate. Many think they’d see lights, gods, judgment — but for him, it was nothingness followed by stillness, and then quiet return.

He says he died for ten minutes… came back, and said it felt like “a peaceful sleep.” Nothing more surreal. https://twitter.com/SignalStudies/status/1690347829011— Signal Studies (@SignalStudies) August 16, 2025

Inside his collapsed heart and lungs, scans later revealed blood clots the size of a cricket ball, the kind that could’ve killed anyone in an instant. Surgeons removed them. But the quiet shadow of what just happened — dying, coming back — haunted his recovery. He remembers waking up without pain but with trouble recalling names, even colors. His brother brought him an orange, and he asked, “What color is that?” The battle to grieve what he lost began with walking, regaining bladder control, and movie-quote therapy to jog memory as reported in The Tab’s follow-up overview.

Today, he runs at “75 percent” of himself. He’ll be on blood thinners forever. He’s physically changed, but more importantly, so has his mission: championing blood donation, particularly within Black heritage communities where donor representation is urgently needed. He now credits the transfusions as lifesavers, not just treatment — a salvation rooted in someone’s compassion emphasized in the UNILAD follow-up.

Matthew’s story joins a long line of near-death survivors. Consider Al Pacino, who almost died during a Covid crisis, describing how he “didn’t have a pulse” and woke to medics in moon suits — no afterlife, just shock and existential reflection as Al Pacino himself shared in The Guardian. Or Danielle Vasinova, actress from “Yellowstone,” whose heart stopped for three minutes during a COVID-induced crisis — she felt spiritually awakened, if unsensational, when she returned with a profound sense of gratitude covered by People.

Three minutes cold and gone. She came back. Said she didn’t go to heaven — but came back more grateful, more rooted. That’s what it does. https://twitter.com/DeepSpaceFiles/status/143127458922— SkyTruth (@DeepSpaceFiles) September 2, 2023

But Matthew’s return wasn’t a cosmic wake-up call or a brush with angels. It was silence, then breathing, then rebuilding. His was neither the “light at the end of a tunnel” narrative nor a spiritual epiphany — just quiet peace and gratitude for every breath that followed.

The science behind such recoveries is intriguing. “Lazarus syndrome,” for example, describes people who are resuscitated after death was declared. Some stories defy explanation: pulses returning minutes after resuscitation stopped, bodies reviving in mock morgue settings as detailed in medical literature on the Lazarus Phenomenon.

But Matthew didn’t stand trial for medical anomaly. He just woke up, still himself, with a mission: raising awareness about blood donation, especially in communities where ethnically compatible blood is scarce. NHS Blood and Transplant emphasizes how vital this diversity is — a reminder that many lives, like Matthew’s, depend on it underscored in the original UNILAD reporting.

This is not just a dramatic anecdote — it’s a jolt to how we hold everyday signs. When our bodies whisper something’s off, we can’t always hear it amid the noise of career, kids, gym schedules. But what if that whisper is a dying heartbeat begging for attention?

Matthew’s message is simple: trust your body. Those tiny glitches — a blocked swallow, swollen feet, unusual fatigue — may be nothing. But they may be everything. His second life didn’t start with divine vision or redemption arc. It started with doctors who didn’t relent, a brother teaching movie quotes, and donors whose decisions carried hope. “I’m so lucky to be alive,” he says, every day, starting from that peaceful awakening.