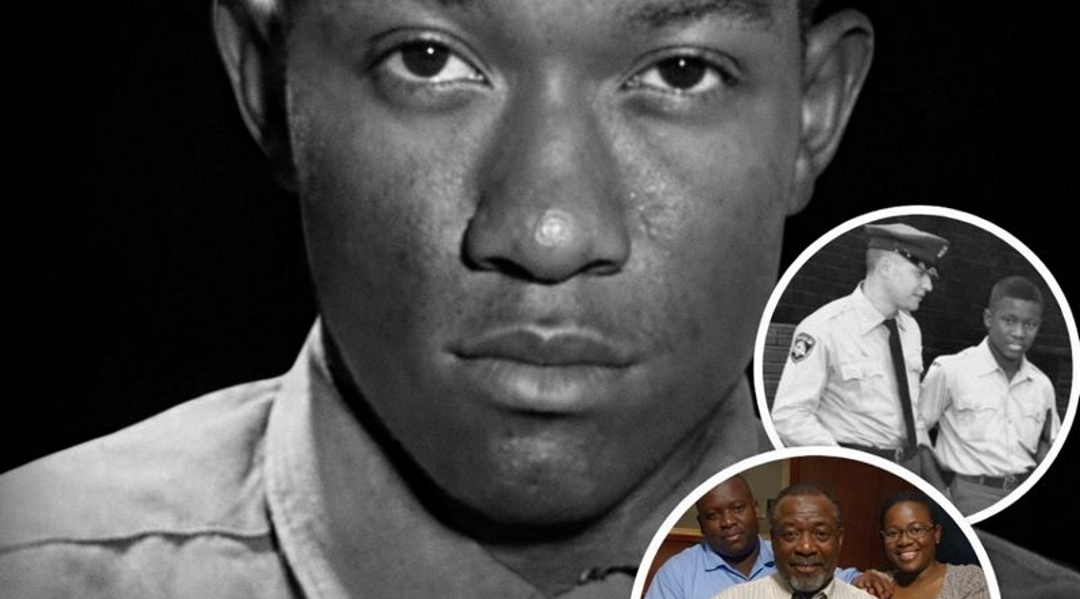

At the time of his trial, the teenager was denied effective legal representation, a failure that scholars say was common in capital cases involving Black defendants in the Jim Crow era. Court transcripts reviewed in criminal justice research reveal that juries were often all-white and proceedings rushed, with little regard for due process.

Family members who attended the exoneration hearing described a mixture of relief and grief. While the ruling restores his name, it cannot undo the execution or the decades of stigma that followed. Advocates emphasized that acknowledgment from the court is meaningful, but it comes far too late.

The case has reignited debate over the death penalty and racial bias in the justice system. Data compiled by death penalty researchers shows that Black defendants, particularly in the mid-20th century, were disproportionately sentenced to death in cases involving white victims.

Legal historians note that wrongful executions represent the most irreversible failure of the justice system. Unlike prison sentences, death leaves no room for correction once carried out — a reality underscored by this case and others examined in exoneration reports.

While no apology or ruling can restore a life taken unjustly, supporters hope the decision will serve as a warning and a lesson. They argue that confronting past failures is essential if the system is ever to prevent future ones.

Seventy years too late, the truth has finally been entered into the record. What remains is the weight of knowing how long justice was denied — and how many others may never receive it at all.